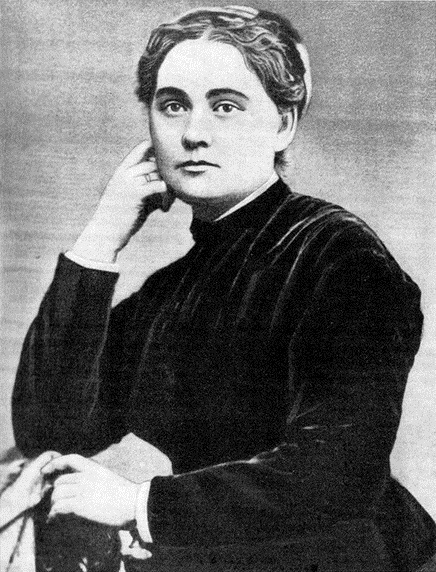

In the weeks before Taras Shevchenko's death in 1861, Marko Vovchok (Maria Vilinskaia, 1833-1907) wrote Shevchenko from Rome. She had heard he was ill; she urged him to wear his cap and to avoid catching cold. She reminded him that he was a father to her; she described to him the majesty of the Colosseum. In this vignette, published in How Languages Changed My Life (Archway 2019), Rory Finnin imagines this pivotal juncture in her life from her first-person perspective.

Do not climb higher, they told me. The ancient concrete steps were steep and fickle; I would lose my footing. There was a damp chill in the morning air; I would catch my death.

But I had not come to Rome to stand still. Above the travertine archways of the Colosseum, there is a top tier whose walls envelop the amphitheatre like the arms of a lover prone to jealousy. It is called the Maenianum Summum in Ligneis. The High Wooden Gallery. Emperor Domitian, with a wave of his hand, added it years after the original construction to corral two groups of spectators: women and slaves.

Treading there slowly, my arms spread like antennae, I stared down at the pockmarked concentric circles of the Colosseum floor. Even in ruin they radiated tyranny and fear. Silently, as if in urgent prayer, I began to mouth a letter to a dead man. The letter of a woman to a slave.

I did not know Taras Shevchenko had died. I just felt it keenly, like a subtle change in the weather. But the letter my lips composed along the Maenianum Summum in Ligneis pretended otherwise, protesting my grief like a thief caught in the act. I implored my dear Taras to guard himself against the elements, to close doors to ward off the draft, to take care of himself. I described for him the heights of the Colosseum and the windows puncturing the walls around me. Fodder for his next poem or painting, I thought, as my throat began to swell.

The crying came slowly, an old steadfast companion. Men who fell in love with me likened me to a sphinx, cold and inscrutable, but they were simply unaccustomed to a woman distracted by a desire to change the world. Change had finally come, and so had my tears. Days earlier in Saint Petersburg, on the 19th of February 1861, it had been decreed that twenty-three million souls were freed from slavery. Serfdom in the Russian Empire, the craven system that had marked human beings like Taras Shevchenko as disposable property at birth, was now gone. Did he live to see it fall?

It was a system I helped to destroy. My stories slung stones of moral clarity at the Tsar’s Winter Palace. I wrote them in a language that was not my native tongue. One after the other, these stories helped bring down a towering edifice of brutality in our society. And as I travelled through Europe, from St Petersburg to Dresden and from London to Rome, my hosts became fond of introducing me as the Russian Harriet Beecher Stowe. The comparison honoured me, but it overlooked an important difference. Stowe wrote in her own name; I did not. My work bore the name of a man.

‘Marko Vovchok’, I remember the writer Panteleimon Kulish muttering under his breath, as if asking himself a question. It was then 1857. He was sitting next to my husband Opanas in Kyiv, hoping to take his place. ‘Marko Vovchok’, he said more clearly, standing up from his chair. ‘Vovchok, ‘Little wolf’. Noble, with a touch of ferocity. It suits your temperament.’

I held my tongue.

‘And vovchok calls to mind movchok, “silence”,’ Kulish continued, now pacing around the front room, his hands tucked in his jacket. He was handsome, with a rough grooming that reflected both his arrogance and his poverty. ‘I have never encountered a quieter woman.’

I smiled, meeting Kulish’s eyes. He held my gaze for a moment before turning back to read the ink-stained pages once more.

‘And Opanas, you had nothing to do with this?’ he asked, head down, scanning lines with his finger. ‘Marusia wrote these stories?’ He used the Ukrainian diminutive for my name Maria, not without sarcasm. ‘In our language?’

‘Ukrainian is her language now,’ Opanas replied, reaching for my hand. ‘The stories are hers, and hers alone.’

Kulish looked up, amused at my husband’s earnest testimony.

‘A Russian debutante who writes so beautifully in the peasant’s Ukrainian?’ he said with a grin. ‘A miracle.’

He placed the pages in his briefcase with care. ‘But the name Maria Vilinskaia Markovych will not sell these stories. ‘Marko Vovchok’ will.’

It was the first moment I would encounter it – this peculiar combination of glowing praise and suspicious disbelief. My stories invited readers not only to hear the voices of serf farmers, toilers, and servants, but to assume these voices themselves, to speak their words, to see the world from beneath the yoke of servitude. These voices spoke Ukrainian around me, so I wrote in Ukrainian.

I learned the language by learning to listen. It did not come easily. While in finishing school in Kharkiv, I heard Ukrainian spoken in kitchens and cellars, in fields and backstreets. The language was ever-present but somehow distant from me, a hazy uncharted sea encircling my Russian-language island. One day, in 1851, I decided to begin to swim.

I was only eighteen years old, and I was in love with an outcast. Opanas Markovych had been exiled from central Ukraine to my hometown of Oryol in Russia for being a part of a secret society devoted to the liberation of serfs in the Empire. He looked the part of the distracted idealist: ruddy complexion, impatient air, eyes that saw through you. He was not rich. He did not drone on about careers or land or standing or glory. He was in the thrall of causes and ideas. While my other suitors boasted about fortunes and follies in St Petersburg, he moved among the local peasantry, collecting and transcribing their folklore and folk songs in the countryside. He walked his own defiant path at a time when I was beginning to walk mine. We were married within months. It was exhilarating.

We moved to Ukraine and settled near Chernihiv, in a verdant slice of territory alive with folk culture between the Dnipro and Desna rivers. Opanas worked at a local newspaper for a pittance, but his real compensation was the chance to visit with local kobzary, old minstrels who sustained the lyrics of the Ukrainian people through music and song.

Eyes beaming, hand possessed, Opanas wrote down their words in a brown pocket notebook tied together with string. The kobzary were at first thrown by his eager interest and attention, but it was not long before they began to drink in his compliments and sing with purpose, heads held high, voices projected into the distance. Sometimes, as a song faded into its final note, you could see them sigh in relief, as if forcing aside the anguish of the present in order to feel the past move through them, the long-forgotten touch of a mother after a fall.

Unlike my husband, I had no pocket notebook. I had no eager look about me. As a foreigner, a Russian woman of some social standing among Ukrainian serfs, eagerness could elicit fear. I simply kept my eyes open. I smiled and said hello, ignoring no one, forcing nothing.

Over time, my presence no longer invited as many downcast gazes or hurried exits among the local peasant women around me. On Saturdays I joined them along the banks of a tributary of the Desna to wash laundry. Week after week, they pleaded with me not to soil my apron or callous my hands in the cold water. They insisted that I let them clean our clothes. I refused politely, time and again, asking them instead where the water was cleanest. They usually pointed me upstream and congregated downriver, where they fought through the silt in the shallows.

One day, this ritual ran its course. Three serfs from the estate of a certain Rozumovsky brought their baskets to the riverbank and knelt down next to me. We exchanged glances. I said little, retreating back to the laundry and to my reflection in the water. Then they began to speak.

I did not eavesdrop. Olesya, Odarka and Ustyna conversed with one another freely, expecting me to listen. They were three of Rozumovsky’s house servants, no older than sixteen. As we kneaded our clothes against the rocks, they recounted Rozumovsky’s movements back and forth to St Petersburg – he was rarely home – and chided each other about the young men from the foundry who had tried to speak to them in church. They were prone to laughter. At times they sang.

But when they made mention of Pani Rozumovska, the lady of the estate, they spoke in breathless, agitated whispers.

‘Pani takes with a smile and gives back with the belt,’ Odarka once said.

Then Ustyna, ‘God have mercy.’

‘She whipped me for letting the candle die out during prayers last night. She called me a sinner,’ Olesya reported.

And Ustyna, ‘The devil always hides behind a cross.’

‘She beat old Paraska to a pulp for picking apples and giving them to the village children,’ Odarka recalled. ‘She called her a thief and struck her across the face so hard I thought her head would come clean off.’

Olesya replied, ‘Pan Rozumovsky, God bless him, would never dare touch an old woman like that.’

‘But he is guilty who is not at home,’ Ustyna said.

Every week, listening to these exchanges, I became more intimate with shame. Shame at my naiveté for not knowing such suffering, shame at my shock when hearing it discussed so openly. I was only a few years older than these girls. I could have been any one of them. All of them seemed to understand our arbitrary fate. They looked on me knowingly, even with pity, but Ustyna’s eyes also conveyed a quiet demand that would change my life. Bear witness to us, they urged me.

With time, I became their friend. I began to carry their stories with me. After our visits, I noted down every new Ukrainian word, expression, and proverb at home. I used their turns of phrase in conversation with Opanas, who soon spoke only Ukrainian with me. Often I sounded like Olesya and Odarka, full of observation and description. Sometimes, at my most vulnerable, I sounded like Ustyna, hesitant and searching. I was developing a new voice in a new language, shaping a new self that empowered me with a sense of boundless potential.

Panteleimon Kulish named this new voice ‘Marko Vovchok’. He helped me publish my stories in Saint Petersburg in 1858, and their effect in shaking the moral conscience of the Empire was almost instantaneous. Readers had never encountered prose with such urgency and first-person immediacy before. Many put down the text disquieted and newly committed to the cause of the liberation of serfs. Others could not bear the scenes of violence, which I did not depict from a convenient remove or as the sole domain of savage men. My heroines were women, but so too were my villains.

None other than Ivan Turgenev raced to translate my stories into the Russian language. Lev Tolstoy and Aleksandr Herzen sought me out in the hopes of collaboration. But as the fame of Marko Vovchok grew, with the institution of serfdom and the wealth of countless landowners in jeopardy, so did murmurs of fraud and deception.

I could not have learned the Ukrainian language in only a few years, some alleged. The Ukrainian voices were too authentic; a Russian like me could not have rendered them so well. The language was too organic and too natural; my husband must have helped me.

One prominent publisher went so far as to proclaim that I was a ‘brazen Russian thief who had stolen a wreath of laurels from the real Ukrainian literary genius’, Opanas Markovych.

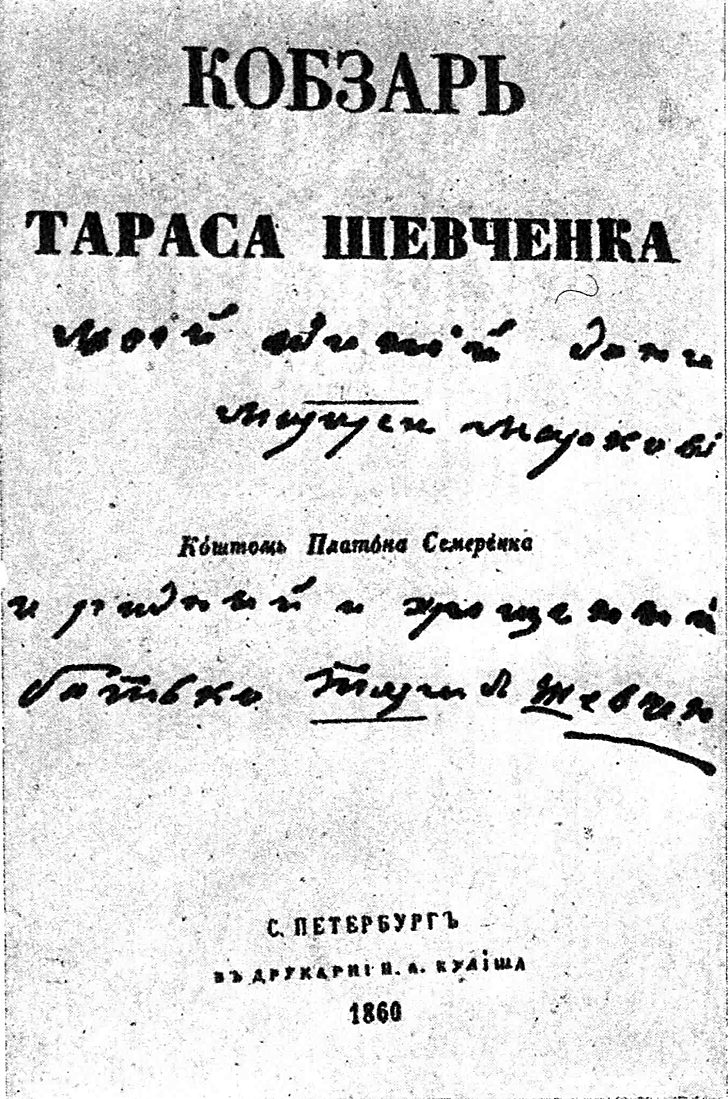

It mattered little to these sceptics that my husband attested to my authorship constantly, everywhere. Even when we began to grow apart, Opanas never ceased to celebrate and promote my work among the Ukrainian civic activists in Kyiv and among the Russian intelligentsia in Saint Petersburg. But the Ukrainian doubters persisted in their claims – until my dear Taras Shevchenko dedicated a poem to me.

Shevchenko’s artistic gifts had freed him from serfdom as a young man, but they also helped cast him in fetters when he was older. His poems in the Ukrainian language condemned the Tsar for imperial crimes and injustices with such righteous fury that he was brutally exiled and forbidden to paint or write for a decade. He returned to Saint Petersburg when my stories first appeared in print, a worn-down shell of his former self.

Without Shevchenko, there would have been no Ukrainian literature for me to take in new directions. His word had become sacred prophecy for Ukrainians across the Empire. He had certainly heard the rumours about me, about the Russian interloper who professed to have mastered the Ukrainian language. He could have dismissed me as a woman passing off her husband’s work as her own. He could have let doubt set in like the mortar in these Colosseum walls. Instead, Shevchenko declared his faith in me in a poem entitled ‘To Marko Vovchok’:

You are my holy star! Shine down on me, burn bright, And bring back life to my weary Heart, wretched and exposed.

His verse concluded with a simple affirmation, one that made clear to all that Marko Vovchok was no man: ‘You are my daughter!’

As I descended from the Maenianum Summum in Ligneis, navigating this paddock for women and slaves, I impatiently wiped away my tears. I wanted to see the execrable remains of empire more clearly. Centuries ago, I thought, Taras Shevchenko and I would have stood together here, a family. We were bound to each other not by origin or ethnicity, but by a common moral conviction, a desire to represent the voices of the poor and the foreign, no matter their language.

‘Farewell,’ I said to him aloud, my voice resonating against the ruins.

‘Do not forget that you are my father.’

'Women and Slaves' by Rory Finnin (How Languages Changed My Life, Archway, 2019)